24 March, 2025

Looking Again at Business Rates Reforms

by Josh Myerson

Learn more

1 July, 2024 · 6 min read

Tax systems are, by their nature, controversial. But few parts of the British tax system have been as contested recently as “Non-Domestic Rates” (NDR), more commonly known as Business Rates. And with the UK General Election taking place this week, it is no surprise that each of the major parties have said they will change the system – to varying degrees – if elected.

Some version of a local tax for local services based on the “rateable value” of a property – how much it would cost to rent it for a year – has existed since the 16th century. The current system, though, really dates from the late 80s and early 90s, when the domestic and non-domestic parts of the system were separated and the ‘multiplier’ – the figure by which the rateable values are multiplied to produce the rates due – set centrally. (Before that, local authorities could choose their own figure).

The controversy around what seems, on the face it, to be a simple tax revolves around a few issues, all highlighted by how the market has shifted in recent years. Put simply, retail rents have fallen sharply in response to competition from e-commerce, which as it has no physical presence on the High Street does not pay the same level of business rates. The system has been slow to react to these changes and may have added to the problems faced by different sectors. What’s more, the underlying inflexibility may affect other sectors in coming years, given the extent to which rents have moved in some sectors recently.

So, what are the problems?

Firstly, valuations are several years apart – historically five, which was reduced to three in last year’s Non-Domestic Rates Act. Given how fast the property market has moved in recent years this has meant that business rates can remain high even while sectors are hit by cyclical or structural headwinds, a problem compounded by the fact that new business rate regimes take effect two years after the actual valuation date.

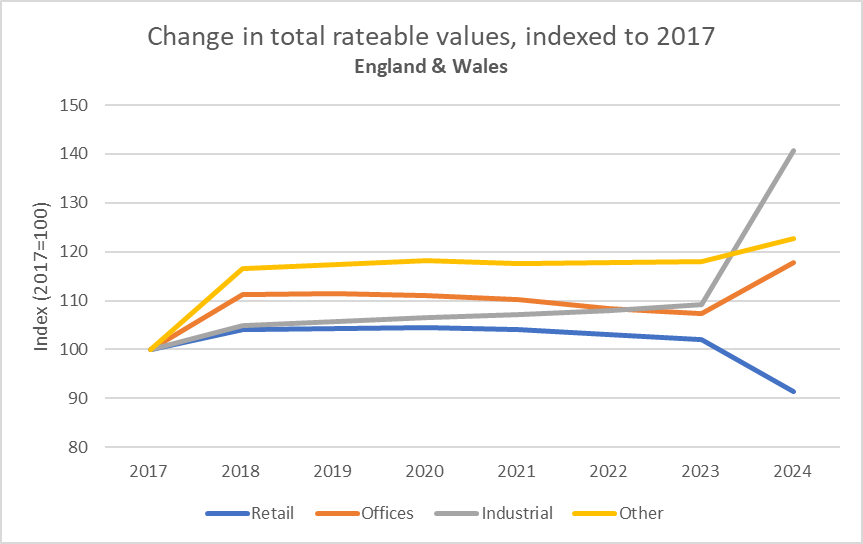

This has been a particular issue in retail markets where turnover fell rapidly as e-commerce expanded. Rents began falling, but as rates remained stable they took up an increasing share of business expenditure, making some locations unviable. (Offices may face a similar issue in the next valuation, although as issues in this sector are less related to business viability and more to changes in working patterns, it is unlikely to have a comparable effect). The chart below illustrates some of the problems, demonstrating how the total value of the various sectors have changed, indexed to 2017 values, when they began diverging. There is also a regional element to this; rateable values in Inner London and the South East have risen by 27% and 21% respectively, but in the North by just 7%.

Source: Valuation Office Agency

This problem was historically exacerbated by “transition”. Large upward and downward changes were smoothed over several years, although in practice this was usually only relevant for smaller properties (rateable value of less than £20,000) where the threshold was set at 5% in the first year following the revaluation. For larger properties (rateable value of over £100,000), with the threshold at 30%, this was less relevant unless there were very sharp changes between valuations.

This, for the reasons mentioned above, has been the case for some parts of the retail sector over the past decade. The very sudden loss of viability in some secondary shopping centres in less affluent parts of the country meant that some owners of vacant properties, or owners of vacant properties, were still paying relatively high rates that did not reflect current values (it is worth noting that rates still apply to empty properties, leaving owners with a significant liability which is only partially alleviated by reliefs of a few months). However, the Treasury ended downward transition in 2023.

A further retail-specific claim is that the system does not produce a level playing field, as online-only retailers do not pay the high rates associated with retail premises. However, it is worth noting that with retail rents decreasing over the past few years, and industrial increasing, the business rate liability for the two sectors will gradually change accordingly. Meanwhile, the vacancy levels on many High Streets have highlighted a further issue impacting landlords – that while there are various time-limited reliefs for empty properties, they are largely still liable for business rates on the full rateable value of the property.

Clearly, the various parties think the reforms of the past few years have not been sufficient. Josh Myerson, who leads Montagu Evans’ rating team, explains; “A few years ago, the Labour Party seemed to be heading towards abolition and replacement, but the language has softened recently (including in the manifesto). The industry is speculating that any new system would remain fiscally neutral, but would use a fixed rather than a floating multiplier, albeit one that might differentiate between different uses”.

“It remains entirely possible that a Labour Government could take retail out of the system entirely and apply a sales tax instead. As for empty rates, the mood music appears to point towards a tightening rather than a loosening of the existing regime.”

A fixed multiplier might remove a strain within the current regime that might become more significant over the coming years. The Treasury has historically insisted that the tax be “revenue neutral”, i.e. that it remains the same (in inflation-adjusted terms) between two valuation dates, through adjusting the multiplier. This means that if rateable values fall overall, perhaps if the date falls during a property downturn, then the multiplier increases to compensate. It seems like that the aggregate stock of office and retail property will fall a little over the coming years owing to shifts in location and the type of demand. Whlie industrial and alternative sectors are set to grow, this may not be enough to compensate, meaning an increasingly disproportionate share of the rates bill would fall on these sectors if the current system is retained.

The Conservative manifesto does not promise such extensive reform, as the current Government has only recently conducted a Fundamental Review, but it does say the party would support “high street, leisure and hospitality businesses” by “increasing the multiplier on distribution warehouses that support online shopping over time”, as well as providing more reliefs for small businesses. This is despite the fact that the Review explicitly rejected differential multipliers.

They also promise to create more Freeports and Business Rate Retention Zones (see below). Meanwhile, the Liberal Democrats are backing a much more radical proposal – removing Business Rates altogether and replacing them with a “Commercial Landowner Levy” which they say will “help our high streets.” This would be a tax based on the land value and would be levied on the landlord, although sceptics might suggest that that would be passed on to the tenant.

The possibility of more localisation of business rate revenue is not mentioned in any of the manifestos, except for the Conservative proposal to create more freeports. While Business Rates were historically collected locally but reallocated centrally according to a complicated formula, more recently councils have been allowed to keep more of the uplift from an agreed baseline. Some would argue that more relocalisation would incentivise development, reduce “nimby”-type sentiments against industrial or data centre development (for example) and generally encourage councils to be more pro-development.

There has been speculation that Labour might review council tax bands, as unlike income tax (for example) they do not explicitly promise not to raise it in the manifesto. There is however no specific mention of the antiquated system, which still uses values from 1 April 1991, meaning the top band is for any property worth over £320,000. This means that in London (for example) the owner of a large house in a central borough, worth several millions, can be paying the same as a tenant in a small flat nearby. This could clearly help ailing local authorities raise more revenue (or at least raise it more fairly). The only reference is in the Conservative Manifesto – a promise not to do it, perhaps a reaction to this speculation. More recently, senior figures within the Labour party have ruled reform out.

Given that at the time of writing the Labour Party seems highly likely to become the next government, we can expect, therefore, a system which still looks very much like the one we have now, albeit with some significant tweaks. But radical changes to either business rates or council tax look unlikely at present.

“The industry is speculating that any new system would remain fiscally neutral, but would use a fixed rather than a floating multiplier, albeit one that might differentiate between different uses”

30 January, 2025

by Bruce Wilson

Learn more

16 December, 2024

by Lucy Markham

Learn more

2 October, 2024

by Samuel Blake

Learn more