30 January, 2025

Business Rates Reform to Support UK Growth

by Bruce Wilson

Learn more

3 July, 2024 · 6 min read

If Labour do – as polls suggest – win a majority later this week, it is clear that planning reform and boosting housing delivery are at the centre of their domestic agenda. But the real barrier to their aspirations may not be Home Counties NIMBYs, rather the extremely bare staffing levels within planning departments.

According to the Royal Town Planning Institute’s annual “State of the Profession” survey, the number of planners in local authorities fell by a quarter between 2009 and 2020, while salaries have fallen sharply in real terms. The evidence also seems to suggest that more senior planners – who may have more experience in drawing up local plans or dealing with complex applications – are more likely to have left the profession, presumably because their higher salaries represented an obvious cost-saving target.

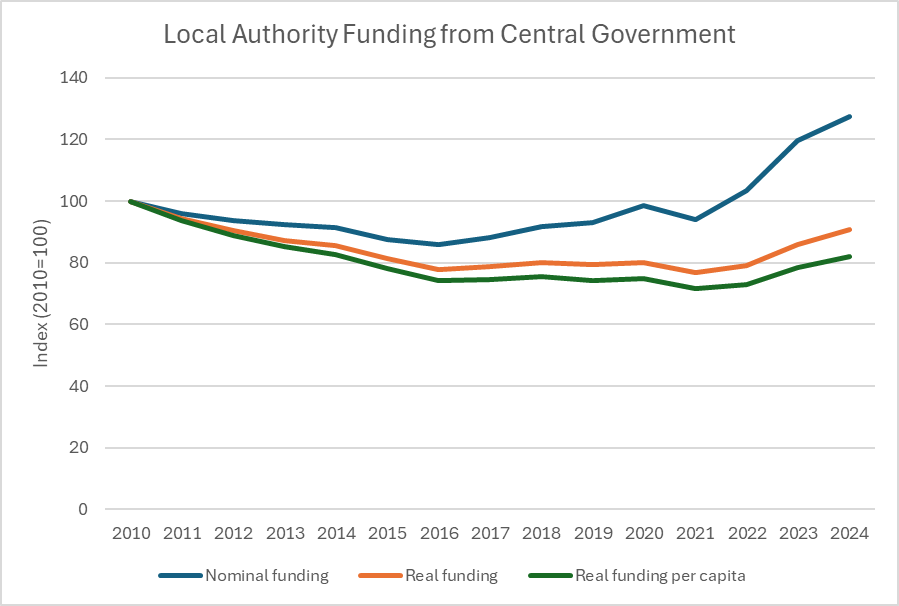

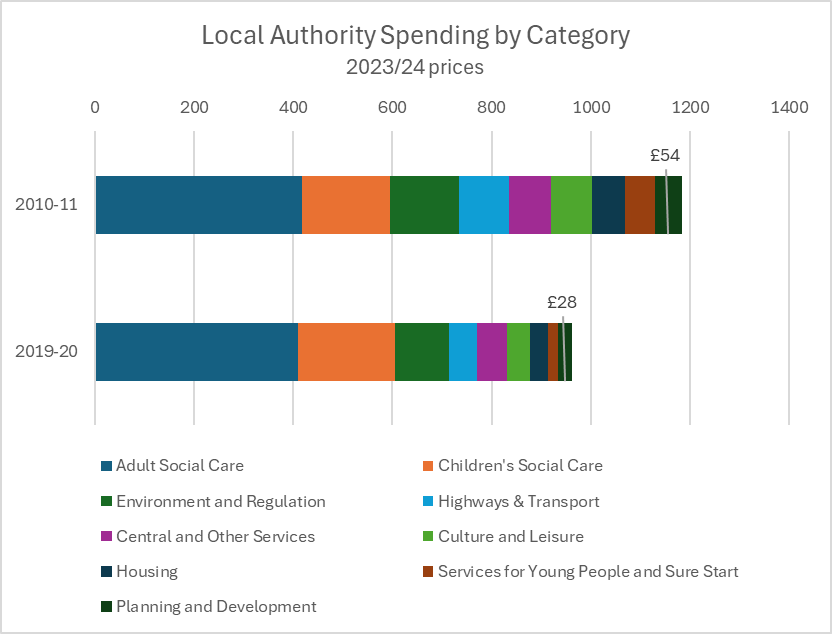

The reasons for this are twofold. Firstly, central government grants to local authorities – which used to be their major form of funding – were reduced sharply during the 2010s. According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the budget of the then Department of Communities and Local Government (now the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities) fell by over 50% in real terms between 2010/11 and 2015/16, the highest of any department. In next place was Work and Pensions at around 35%, with some department – health for example – seeing real terms increases.

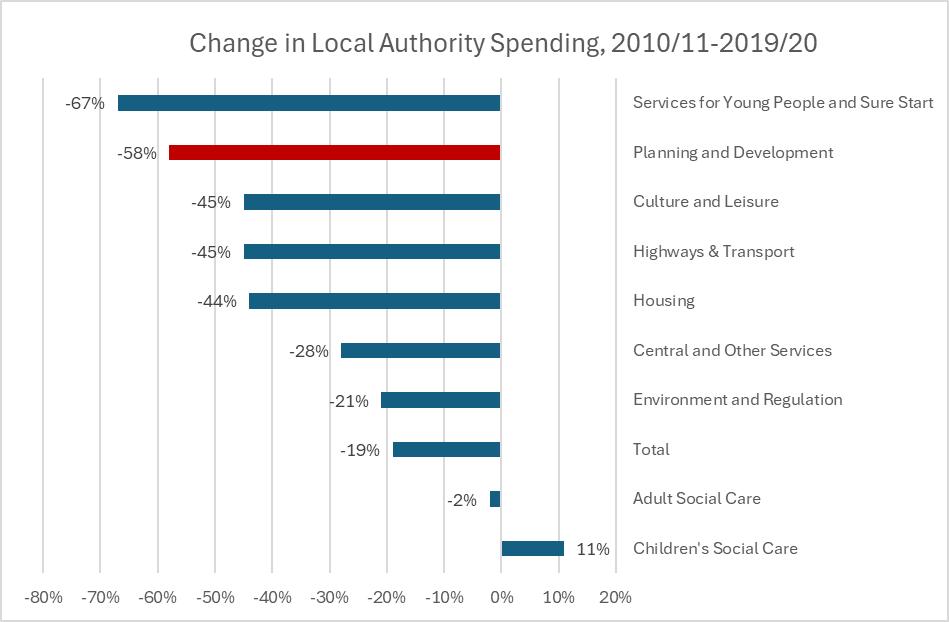

Councils could increase council tax but could not enough remotely to compensate. Their response was to prioritise statutory services such as social care, which have taken up an increasingly large portion of council budgets. According to other IFS figures, total spending per head fell by 19% between 2010/11 and 2019/20, but for Planning and Development Services it was 58%. For adult social care, however, the figure was just 2%. (Increasing planning fees has moderated this, but again very marginally).

If Labour wants more housing without significant changes to the system, it surely means more planning applications. This either means more work for existing planners (who are already increasingly leaving for the private sector blaming workload and conditions) or more planners. With Labour also hinting that they will bring back regional-level planning (or at least some level of spatial planning that is larger than local), this implies a need for experienced staff over and above the numbers needed to process applications. And even if the next government does pursue streamlining measures such as Development Corporations, they still require staff.

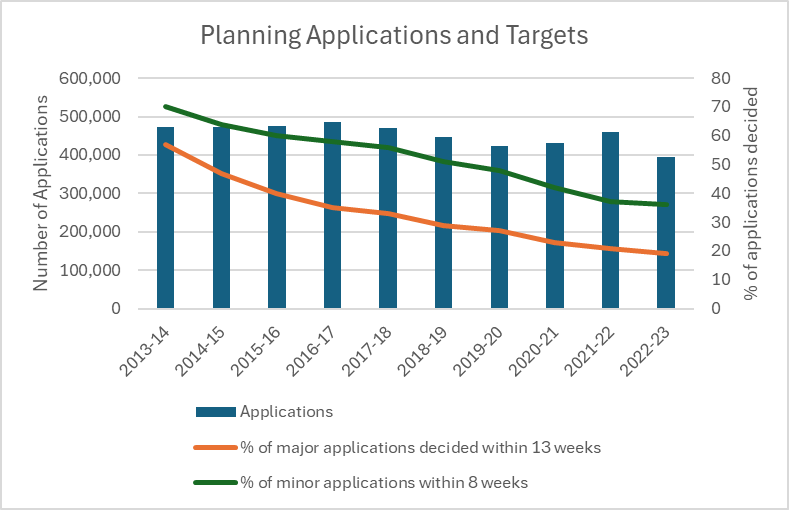

This might seem an achievable stretch if the current system were coping with the remarkable fall in funding and planner numbers seen over the past decade. But the data and anecdotes suggest that this very much not the case. The number of applications has dropped slightly over the past 10 years – which may reflect a higher tendency to pre-application discussions rather than a drop in activity, until recently at least – the % of applications decided within the relevant timeframe target has dropped like a stone.

In 2013/14, some 57% of major and 70% of minor applications were decided within 13 and 8 weeks respectively. This fell every single year, without fail, to stand at 19% and 36% in 2022/3. The shift is clear in the graph below. And meanwhile, as has been widely reported, over three quarters of English councils do not have an adopted, up-to-date plan. So, in some ways, “proper” strategic, spatial planning has been hit harder than development control, even if that has suffered too.

These figures may be the tip of the iceberg. As Rachel Power, Partner in Montagu Evans’ planning team, says: “It is not uncommon for a pre-application meeting to be held up for up to 4 months after the submission of the pre-application request, with applicants having to wait a further four months for formal written feedback from the meeting.”

The percentage of applications failing to meet the targets perhaps also fail to show how long the process can sometimes take. “In one instance, a local planning authority took up to 18 months to determine a single storey extension to an office building, whereas one London borough took three months to validate the receipt of a prior approval application, so the 8 week decision period expired before the application was registered, and therefore consent was automatically issued.” It has become increasingly difficult to speak to officers, as they are busy dealing with historic backlogs and cannot address new applications.

It is clear, then, that the system has become so poorly funded that it is failing to function. Fingers could, of course, be pointed at the complexity of the British planning system and the level of documentation required, but even with dramatic changes it is hard to see how planning could have continued to function well given the scale of cuts that have had to be imposed.

This not only matters in terms of achieving higher housing numbers. It is also about delivering homes and commercial facilities, from distribution warehouses to data centres, in the right places, ensuring they are sustainable and attractive, and co-ordinating it with infrastructure and amenities. This will require, as the manifesto recognises, proper ‘planning’ (rather than simply development control) which is not subject to the priorities of one local authority. It is also talking about New Towns and the wider use of CPO powers which would also place additional burdens on the sector. This, in turn, means not just more planners, but more of those who can bring together plans for housing and other development with infrastructure and understand the economic and environmental trade-offs of different sites.

Clearly, the biggest danger is that much-needed housing and economic development doesn’t appear. But a secondary danger is that any ensuing boom is so badly planned – owing to staff shortages – that it ends up tarnishing both the case for more development and the political legacy of the next government. Labour manifesto does promise 300 new planners, although this equates to 0.95 of a planner per English local authority – so hardly enough to move the needle even if workloads remain the same. Based on its desire to improve delivery and deliver an additional, more strategic, larger-than-local tier of planning, it will probably be hoping that workloads do increase rather substantially.

Of course, these new staff can be directed towards growth areas, but the numbers still seem insufficient, and lack of capacity may remain a major barrier to the next government’s ambitions in this area. Further streamlining of the system could reduce this, but without major legislative reform the problem will remain to some degree. Labour, if elected, are keen to get more housing built – and unblock wider planning-related issues around infrastructure and economic growth – without major reform. Given the time this would take, and the time it takes to build, this would inevitably not produce significant benefits within the next parliamentary term. But this may, in the end, be the only way to get Britain building at the level we really need.

In the meantime, the new Government may have no alternative other than finding a way to fund and prioritise planning departments. Some developers have said they would happily pay higher fees if they could guarantee a faster process, although this may not apply to everyone. There was a planning application fee increase last year, but the funds raised are not ringfenced, despite 88% of those responding supporting the idea that they only be used for planning departments and not to cross-subsidise other functions.

Whatever option is chosen, it is hard to see how to replace the large numbers of highly experienced planners who have left the profession recently, the ones who would have been best placed to help with reintroducing more strategic, subnational planning. That may also require a longer term investment in planning and urban design education and training, although once again, the results might take a while to appear.

Labour may have no choice, given its agenda, other than to find a way to fund and prioritise planning departments.

16 December, 2024

by Lucy Markham

Learn more

2 October, 2024

by Samuel Blake

Learn more

19 September, 2024

by Jon Neale

Learn more