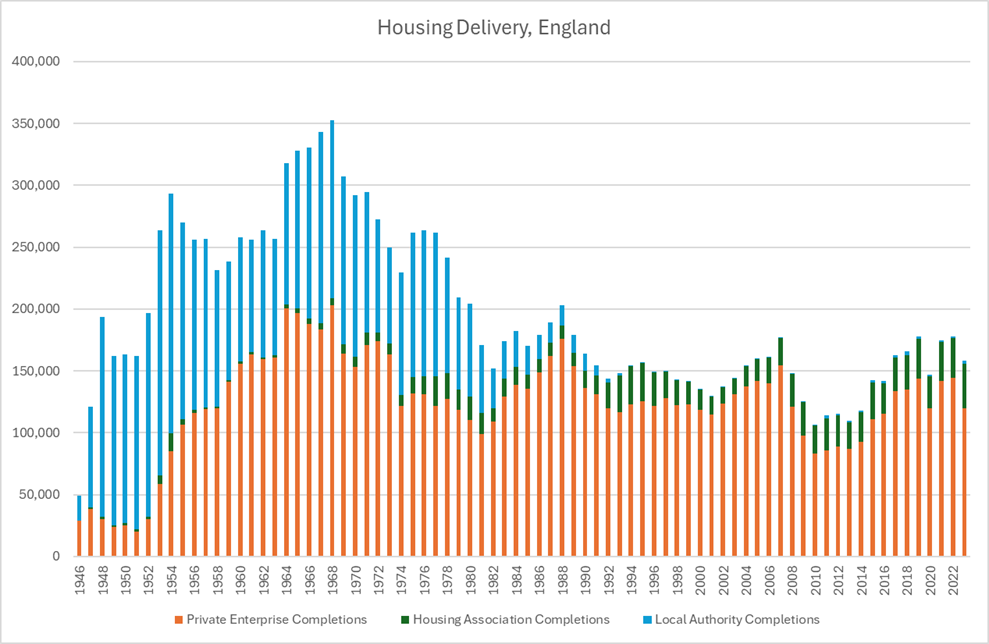

The UK does not build enough houses. That point has been driven home by endless government reports and think tank pamphlets as well as everyday experiences of trying to buy or rent, particularly among young people in the most popular locations A look at the graph below, of housing delivery in England since 1946, shows quite how the delivery of new homes has collapsed since 1966 (almost 60 years ago), which was the last time over 300,000 homes – the government’s current annual target – were delivered. Since the mid-1980s, in fact, the average has been closer to half that.

It’s easy to point at this graph and argue that private delivery hasn’t changed that much, and that the main problem is the massive reduction in social housebuilding. But the fact the graph begins in 1946 (as that’s when the official data does) obscures the very high levels of private sector activity in the 1930s, when it was delivering around 300,000 homes a year. Many would point at that decade and argue that before the current planning system was introduced in 1947, the private sector appeared perfectly capable of delivering housing to meet needs, and has been shackled since by regulatory changes. Others might point at the wider economic picture in that decade, which was unusually amendable to building. However, that debate is for another day. This post is about mandatory, top-down housing targets for local authorities, the Labour Party’s promise to re-introduce them if they become the new governing party in July, and whether they would or could be effective in driving up that woefully low number.

Housing targets have been deeply controversial ever since they were introduced after recommendations in the 2004 Barker Review. The Treasury, under then Chancellor Gordon Brown Labour, had become increasingly concerned about the poor level of housing delivery and the implications for house prices – although at that time it focussed as much on macroeconomic stability (no return to boom and bust!) as affordability. Barker’s review suggested regional targets based on price evidence, all distributed via the regional assemblies which were then tasked with drawing up Regional Spatial Strategies (RSSs). These would guide the local plans (then called Local Development Frameworks) that would identify the relevant sites on which housing delivery would be met.

This all seemed logical (if perhaps a bit bureaucratic to some), but it was not without political tension. The South East and East of England assemblies – effectively organisations consisting of the local councils, as the plans to convert them to democratic assemblies had gone no further than the failed referendum in the North East – reacted in horror to emphasis on price and affordability, which would clearly have driven greater housing numbers to those areas. Nevertheless, targets were set (albeit based more on household formation than on price) and distributed down to local areas.

With the arrival of the Coalition government in 2010, and the formidable figure of Eric Pickles as Communities Secretary, these targets – and indeed the entire structure of regional planning – were abolished. Under his credo of ‘localism’, councils would set their own targets based on the methodology they chose. Given the high levels of demand in some areas, and the allocations required to meet that demand, many councils found it impossible to do anything, and those who did attempt to impose vaguely sensible numbers found themselves dislodged by anti-development political opponents and the emergence of NIMBYism

This all led to the attempted imposition of the ‘standard method’ of devising housing need. This proved no less controversial than the RDA targets and housing became a major factor in the Conservative defeat in the Amersham & Chesham by-election in 2021 and targets were again dropped. Councils were still required to deliver enough land for five years’ worth of housing supply, but as this is backward-looking, it means high-delivering councils have to keep on delivering, whereas underperforming ones have low targets. And that’s before we get to the problem of how few councils have up to date local plans.

This history hasn’t been provided for the sake of it. It demonstrates how difficult an issue housing targets are, even if grounded in evidence and developed as part of a more coherent system of regional planning. From an academic point of view, the methodology is complex and contested, and their imposition is political dynamite. The problem is, as endless opinion polls show, that most people are in favour of more housebuilding nationally (so a national target is politically popular) but most people seem to think it should all be built somewhere else – often pointing to fairly flimsy reasons as to why, for example lack of school places, doctors or infrastructure. It will be easier for Labour to impose these targets on two counts, firstly their electoral base is young (and in need of housing) and secondly it is far more urban.

There is also an implicit suggestion that Labour will reintroduce regional planning. This would make sense as if new housing is to be sustainable it needs to be aligned with where new infrastructure is planned (or where it already exists). Some authorities have more protected land, or more easily redeveloped brownfield sites. Consequently the ability – or desirability – of delivering housing in different parts of a region will vary, even if housing demand needs to be understood in more aggregate terms. Some may even be chosen for sites for the New Towns that Labour is also proposing. This means that housing targets would probably vary to some extent from area to area based on that overarching plan.

Will Edmonds, Partner in Montagu Evans’ planning team and a specialist in large-scale housing development, explains some of the difficulties around reintroducing targets: “Given how central Labour sees housing to its domestic economic programme, targets would need to have some teeth if they were to be effective. Councillors are often under a lot of political pressure to refuse applications, so an automatic award of costs to promoters at upheld appeals where officers recommendation to approve has bene overturned might be one way to redress the balance.”

“And as more of a carrot than a stick, there should also be some financial incentives around housing targets. The New Homes Bonus offered such an incentive, but perhaps it could be extended to full council tax retention for each additional unit; this could be even more effective if combined with a redistribution of council tax bands, although this has now been ruled out by the party.”

Demographics would not completely insulate a Labour Government from the politics of targets (particularly if green and LibDem votes become more significant over the parliamentary term). The emphasis many councils place on affordable housing (rather than market housing) will be a further complicating factor. But the next government will have to ride out these storms if it wants to see improved housing, and more construction, become the political legacy it can use in the next election. Certainly, the other parties are more cagey here.

The Conservatives do not mention targets at all, whereas while the Lib Dems talk of a higher target of 380,000 new homes (including 150,000 new social homes) but give no details on how this would be achieved other than through garden cities and “community-led development of cities and towns”. The problem is, of course, that if you ask communities how much housing they want, they tend to give you a very low figure indeed alongside numerous reasons why their local areas are not suitable to support the deliver f new homes.

A further issue, of course, is whether granting planning consents will quickly lead to a strong uptick in construction. There is little doubt that it would have an effect in the long term, but with mortgage rates still at a recent high, affordability squeezed, and viability still a challenge given hikes in materials costs, the appetite among developers for a rapid increase in delivery is perhaps not that strong. Much will depend on wider economic factors and the trajectory of the mortgage market.