In short, the figures do indeed, as predicted, point towards a lower aggregate demand for offices, but with some locations seeing robust or even stronger activity than before the pandemic. This is particularly the case in Central London. Equally, while the big cities outside London have seemed weaker recently, the gap between their cores and their out-of-town markets appears to have increased. The real challenge, though, is how second-tier cities and towns cope with this new phase of economic urbanisation.

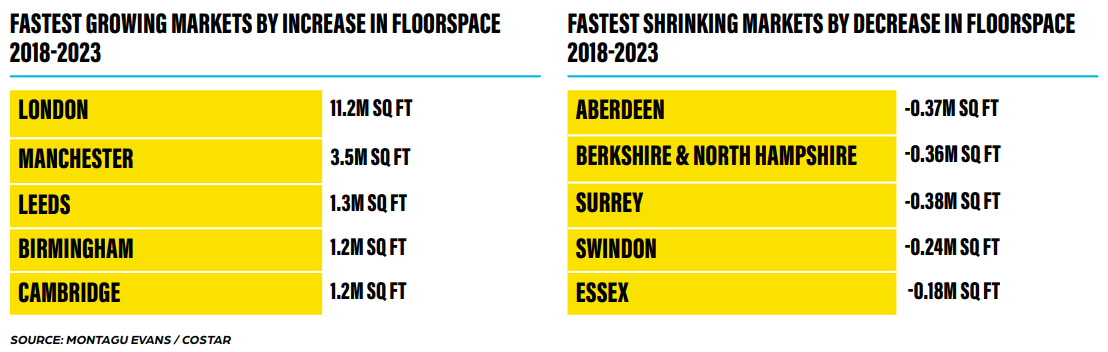

The stock itself has already begun to respond to these trends. As can be seen below, the fastest growing markets over the past five years are London and the other big cities, as well as Cambridge. Meanwhile, the markets which have seen the most significant contraction are largely the out-of-town markets around London, in the Home Counties, except for Aberdeen, which has particular issues given its heavy dependence on the oil & gas markets.

This geographic polarisation is increasingly apparent in market statistics. The highest vacancy rates – at 20% or more – are generally in town or out-of-town locations such as Swindon, Maidenhead and Woking as well as non-central London office markets such as Hammersmith, Docklands and Chiswick. City centres such as Manchester, Birmingham and Bristol also have relatively high vacancy rates – just behind these areas – but this probably reflects where development has occurred over the past few years; it has been strongly skewed to these locations.

Vacancy rates can be misleading, especially if a lot of space is under construction, but in parts of the Thames Valley around 6% of buildings (weighted by size) have been completely vacant for more than a year, whereas Oxford, Cambridge and Milton Keynes generally have virtually zero in this category. This is likely a combination of demand and difficulties related to planning and infrastructure in building here – meaning the supply response is notably more subdued than in cities such as Manchester or Birmingham.